What if they f*cked with your memories?

It's all fun and games until someone loses an identity

It’s 2:17pm. I’m sure the plumber was supposed to be here a couple of hours ago. He hasn’t called or responded to my text. When we spoke on the phone, yesterday, he said “tomorrow at 12”. But did he say “tomorrow” or am I misremembering, and actually he’s supposed to be here tomorrow?

I’m starting to doubt. What if I can’t trust my memory? At what point should reality overrule what is written into my brain? While I wait for the plumber, let’s look at some speculative fiction stories that explore the fallibility of memory.

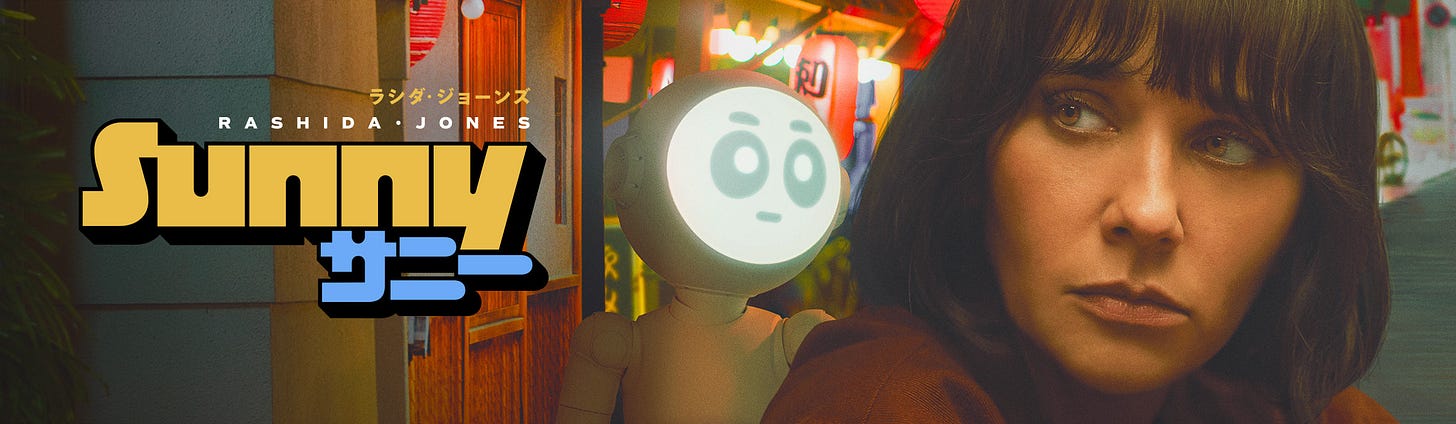

In the Apple TV series Sunny (based on the 2018 novel The Dark Manual), Sunny the domestic robot arrives fresh out of the box, with no memory before that date. But Sunny can do things other robots aren’t allowed to, and people are after her, and the reasons why are locked away behind her firewall.

Sunny mixes science fiction with mystery and dark comedy. It’s a bit of a slow burn to start with, but the plot builds in complexity over the 10 episodes. Episode 9, told entirely from Sunny’s perspective, is reminiscent of the good days of Black Mirror.

Before Total Recall with Colin Farrell there was Total Recall with Arnold Schwarzenegger, and before that was the Phillip K Dick story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale. Let’s say the movies were “inspired by” the story, because they take the premise and run with it. In Wholesale, Rekal, Incorporated can save you the expense of going on holiday by simply implanting the memory of a holiday directly into your brain! What about living out your fantasies? That’s hard, but Rekal has a shortcut.

"Mr. Quail," McClane said patiently. "As you explained in your letter to us, you have no chance, no possibility in the slightest, of ever actually getting to Mars; you can't afford it, and what is much more important, you could never qualify as an undercover agent for Interplan or anybody else. This is the only way you can achieve your, ahem, life-long dream; am I not correct, sir? You can't be this; you can't actually do this." He chuckled. "But you can have been and have done. We see to that. And our fee is reasonable; no hidden charges." He smiled encouragingly.

What could possibly go wrong?

The short story Memories of Memories Lost, by Mahmud El Sayed, explores the opposite premise: memory removal. Voluntary, of course, because memories can be exchanged for cash.

So, last year it was a birthday party. Or, more specifically, a shitty mug that my library colleagues got me for that birthday which said, “Kiss the Librarian.” That’s how it works in the Conservatorship. The Crablegs can’t just reach into your mind and pluck out what they want. They need a conduit, an item to latch onto. You have to offer them something physical—a memento that they can take and keep.

…

It’s strange how memories work. You can’t just take one out without affecting the rest. No, memories are like those out-of-date power cables in the top drawer of your kitchen cabinet, all tangled up together.

Hand over one crappy novelty mug that is too small to even contain a decent cuppa and who knows what else you’ll lose? Give up memories of one uneventful birthday party and who knows what else disappears with it? In my case, it was a band—Pixies. Because Johann was there that night and we sang “Velouria.”

The audio narration by Karim Kronfli is excellent, so pop some headphones in and spend 31 minutes exploring Ahmed’s lost memories. Turns out they’re worth quite a lot…

30 years ago, Pulp Fiction blew our minds with a non-linear narrative timeline, which was something of a novelty. A few years later, Memento took it a step further and made it integral to the plot. You see, Leonard Shelby can’t form short term memories. Which means he finds himself in the middle of a situation without any understanding of what led him there, or what just happened. The movie is told through a reverse timeline, putting the audience in the same situation as Leonard—no context of what came before, chronologically—until we get to the next chapter and see what led up to it.

(As an aside, I wonder if the polaroid within polaroid image used on the movie’s poster inspired the director’s later work, Inception.)

We all love innovative tech companies, right? Like, they’d never invent something without considering the downsides, the possible misuses or unintended harms. So if one of them promised to give us all perfect memory would you sign up?

But even if Remem wasn’t constantly crowding your field of vision with unwanted imagery of the past, I wondered if there weren’t issues raised simply by having that imagery be perfect.

“Forgive and forget” goes the expression, and for our idealized magnanimous selves, that was all you needed. But for our actual selves the relationship between those two actions wasn’t so straightforward. In most cases we had to forget a little bit before we could forgive; when we no longer experienced the pain as fresh, the insult was easier to forgive, which in turn made it less memorable, and so on. It was this psychological feedback loop that made initially infuriating offences seem pardonable in the mirror of hindsight.

What I feared was that Remem would make it impossible for this feedback loop to get rolling. By fixing every detail of an insult in indelible video, it could prevent the softening that’s needed for forgiveness to begin. I thought back to what Erica Meyers said about Remem’s inability to hurt solid marriages. Implicit in that assertion was a claim about what qualified as a solid marriage. If someone’s marriage was built on—as ironic as it might sound—a cornerstone of forgetfulness, what right did Whetstone have to shatter that?

I come back to The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling by Ted Chiang a lot—both in my mind, and as a story I recommend. It’s a great concept, well executed, and has a couple of gutpunches that make the story live on in your (my) head for a long time.

(Ironically, it’s a struggle to access the Wayback Machine version of the story because of the archive.org issues. But you can buy Ted Chiang’s anthologies and all his stories are 🤯😭😍. Like Story of Your Life, on which the movie Arrival was based.)

Honorary mentions also go to Johnny Mnemonic (William Gibson), and A Memory Called Empire (Arkady Martine), both of which involve passing memories from person to person. And “Three Calendars” by Angelique Fawns, published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, about a detective with dementia.

Did I miss your favourite speculative story about memory? What else would you recommend?

The plumber just called to apologise for not showing up. We rescheduled, and he said he’d see me tomorrow at 12. I remember now: that’s what he said yesterday.